Cookies Info

Accept Utilizamos cookies propias y de terceros para realizar análisis de uso y de medición de nuestra web para mejorar nuestros servicios. Si continua navegando, consideramos que acepta su uso. Puede cambiar la configuración u obtener más información aquí: Política de Cookies

- Reconciliación Nacional

- Second Republic

- Post-war period

- War against fascism

- Lucha por las libertades

- Early history

El fin de la experiencia guerrillera y la prioridad otorgada a la movilización social, utilizando entre otras cosas la infiltración en las organizaciones de la dictadura (especialmente las sindicales), pronto empezaron a dar sus frutos. Las nuevas orientaciones, más apegadas al terreno, sintonizaban bien con cambios en la sociedad española, que el PCE no siempre supo interpretar adecuadamente en sus análisis, pero sí consiguió aprovechar con una práctica a la vez tenaz, flexible y realista. El V Congreso (1954) y sobre todo la Política de Reconciliación Nacional (1956) iniciaban el gran viraje, que llevaría al partido a convertirse en la fuerza hegemónica del antifranquismo.

La Reconciliación Nacional (RN) llamaba a superar la fijación en las trincheras de la Guerra Civil, que dividía a las clases populares y apenas sintonizaba con la sensibilidad de nuevas generaciones crecidas tras el conflicto. Pero pretendía, sobre todo, tejer amplias alianzas en los movimientos de masas (especialmente con sectores católicos y nuevas fuerzas emergentes) y avanzar en la unidad con otras fuerzas en el campo político, con el fin de aislar al régimen y conquistar la democracia.

La formulación de la RN coincidía, no por casualidad, con un nuevo clima nacional e internacional. En España, se sumaba al cambio de ciclo que suponían los primeros y prometedores brotes de protesta estudiantiles y, sobre todo, a la todavía lenta revitalización de las movilizaciones obreras que luego, desde 1962, se convirtieron en un factor político de primer orden. En el ámbito internacional, el XX Congreso del Partido Comunista de la URSS (1956) iniciaba la compleja desestalinización y abría paso al fin del monolitismo del movimiento comunista y a la aceptación de la diversidad de vías nacionales al socialismo.

En términos generales, el PCE supo interpretar acertadamente las nuevas condiciones, pese a errores en su diagnóstico sobre la supuesta debilidad de la base social del régimen. El exceso de voluntarismo en ese sentido condujo (en 1958 y 1959) a convocatorias de movilización a fecha fija con exiguos resultados, pero que no afectaron en lo esencial a una política unitaria eficaz en el movimiento obrero y los movimientos sociales. Particularmente, el partido supo interpretar y encauzar correctamente la novedad de las primeras comisiones obreras que surgían en los conflictos más o menos “espontáneamente”. Su estabilización y regularización, junto con el aprovechamiento de los cauces legales y la infiltración en el Sindicato Vertical, fueron las bases de la Oposición Sindical impulsada por los comunistas desde finales de los años cincuenta, que en pocos años rendiría óptimos resultados. Hay que señalar asimismo el compromiso de muchas militantes en las redes de solidaridad con los encarcelados y de denuncia de la represión, una labor en la que con frecuencia se implicaron a partir de su condición de mujeres de presos.

Paralelamente a la reactivación de nuevos frentes (obrero, estudiantil, femenino, intelectual…), tuvo lugar un proceso de renovación en la dirección, que incorporó a luchadores activos dentro del país y también a la generación de dirigentes ya experimentados surgidos de la antigua Juventud Socialista Unificada. Con este cambio generacional que encarnaba, en la cúpula, la figura de Santiago Carrillo (nuevo secretario general desde 1959, mientras Dolores Ibárruri pasaba a ser presidenta), la segunda mitad de los cincuenta y los primeros sesenta fueron años de consolidación y avances ind udables en la implantación del partido.

udables en la implantación del partido.

El VI Congreso (diciembre de 1959-enero de 1960) vino a refrendar la línea emprendida y a poner en marcha el diseño de nuevas tácticas de lucha. El objetivo final, en la estela de las resoluciones del XX Congreso, se cifraba en una “vía nacional al socialismo” definida como “democrática” y “pacífica”. El paso intermedio era la “salida democrática” (opuesta a la oligárquica) al régimen, mediante una ruptura política basada en un amplio movimiento social y ciudadano (la Huelga Nacional), que abriera el camino al derrocamiento de la dictadura y la apertura de una nueva etapa de democracia avanzada.

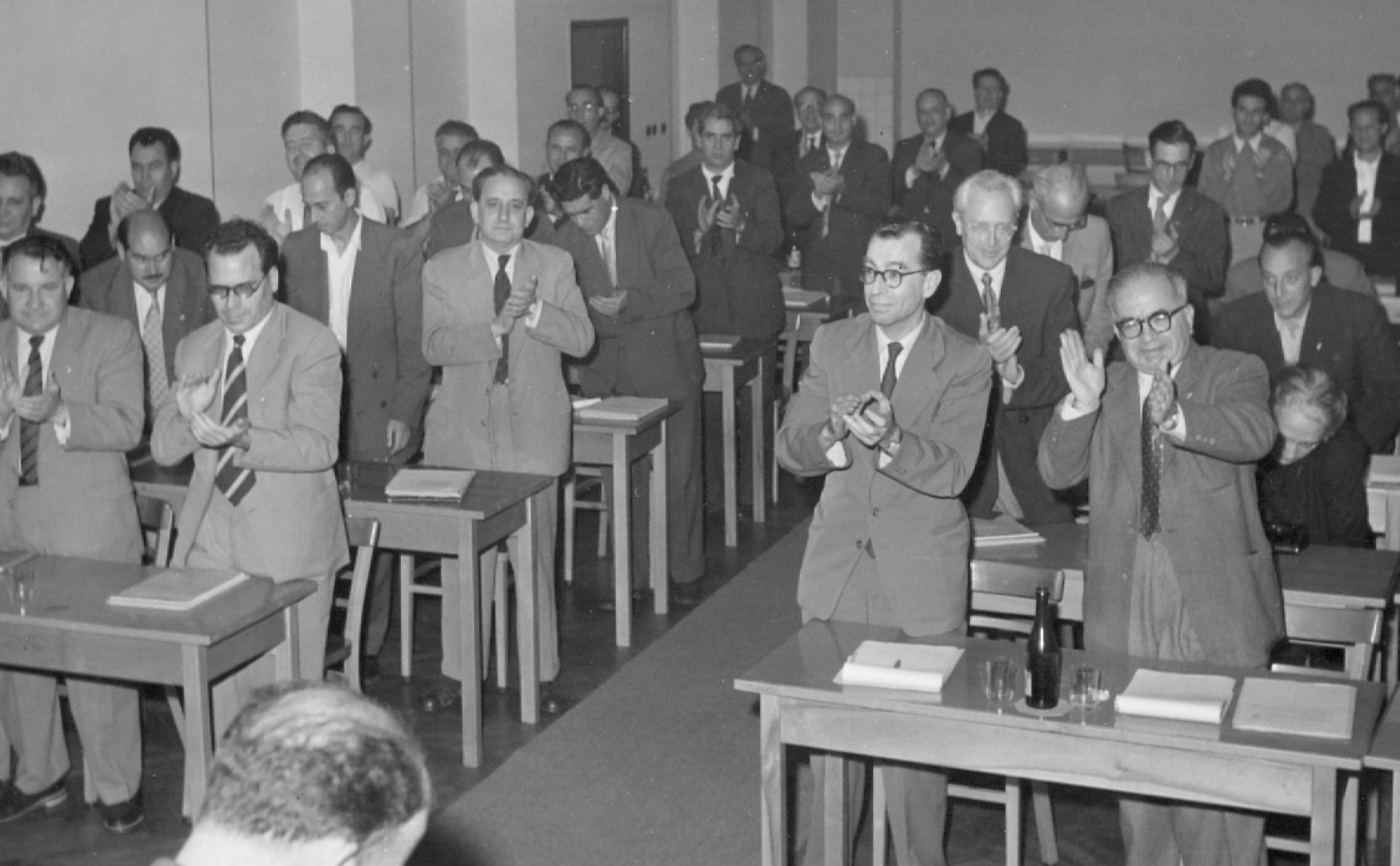

Imágenes del Archivo Histórico del PCE

Foto 1: V Congreso del PCE, celebrado en Bucarest en 1954.

Foto 2: Reunión del Comité Central del PCE en 1957, en la que se abordaría el debate de los sucesos húngaros del año anterior. Entre otros se pueden ver, de izda. a dcha., en primera fila a Santiago Álvarez, Simón Sánchez Montero y Tomás García; en segunda fila a Ignacio Gallego, Josep Serradel (PSUC), Julián Grimau y Dolores Ibárruri (sentada); en tercera fila se distingue a Romero Marín y a Ramón Mendezona.

Foto 3: Mesa Presidencial del VI Congreso del PCE, Praga, diciembre 1959 - enero 1960. En él Carrillo plantea la posibilidad de una vía al socialismo propia, distinta de la soviética, bajo un sistema parlamentario con pluralidad de partidos.

Más en el cuadernillo "De la Reconciliación Nacional a la crisis de la Transición"

During the first half of the thirties, our Party was a small political force, hampered by its limited member base and its marginal character. After experiencing a fast growth during the first year of the Republic, the affiliation fluctuated until it reached between 15,000 and 20,000 members in 1934. Most of them belonged to the working class, although the numbers were small at the time –and the poor results of the elections did not help. The party also had some thousands of members in the youth branch, its own trade union (CGTU) and some newspapers (especially Mundo Obrero), but it paid little attention to feminine affiliation.

During the first half of the thirties, our Party was a small political force, hampered by its limited member base and its marginal character. After experiencing a fast growth during the first year of the Republic, the affiliation fluctuated until it reached between 15,000 and 20,000 members in 1934. Most of them belonged to the working class, although the numbers were small at the time –and the poor results of the elections did not help. The party also had some thousands of members in the youth branch, its own trade union (CGTU) and some newspapers (especially Mundo Obrero), but it paid little attention to feminine affiliation.

It was a small, isolated party, and it barely had any influence. To a large extent, this situation was the result of its initial sectarian tendency and its radicalism regarding the Republic. Our political position was based on accusing the new regime as a “bourgeois” and “counterrevolutionary” Republic, contrary to the interests of both workers and peasants. At the same time, it was consistently and strongly opposed to republican-socialist governments. We thus followed the guidelines of the Third International, which defended confrontation against “social fascism” and “petty-bourgeois anarchism” until 1934, according to the motto “class against class.” The alliance strategy, which defended “a single front from the base,” barely had any results, and standing against the Republic didn’t help capitalize on the discontent felt by workers and peasants alike.

In 1932, the Comintern promoted a change in the leadership of the party. This brought the fall of José Bullejos and the rise of José Díaz as the new General Secretary, leading a new team (Dolores Ibárruri, Mije, Hernández, Uribe, Checa…). This group of people started renovating the party line since 1933, calling for the creation of an antifascist front against the threat of the rise of fascism. Because of this, in September 1934 the PCE joined Alianzas Obreras, together with socialists, and took part in the revolutionary general strike in October 1934. Afterwards, the repressive and reactionary policies put forward by the radical-cedist government enabled joint initiatives among the left and a growing unitary spirit. In this regard, Pepe Díaz advocated for an antifascist “popular block” that defended democratic freedom. This position was validated and strengthened by the strategic shift adopted by the Communist International during its Fifth Congress, when Dimitrov promoted the creation of antifascist popular fronts that brought together working glass forces and all the progressive and democratic sectors of the population.

So when socialists and progressive republicans agreed on the creation of the Frente Popular (Popular Front), the PCE joined without reservation. From that moment on, Spanish communists became strong advocates for the democratic Republic and the unity of the Popular Front. This represented a significant change in the party line, setting aside class identity and further emphasizing a wider collective identity: the “working people,” following the tradition of the republican discourse. It also represented the support of the program for the “democratic-bourgeois revolution” –a wording that should not distract us from the strong popular, working-class content the PCE defended for republican democracy, which should be founded according to the interests and participation of the grassroots sectors.

This new strategy to create a wide antifascist alliance and to defend a democratic Republic contributed to the electoral success of the Popular Front in February 1936 (with 17 parliament representatives that were members of the party), and it also allowed to resist during three long years against the reactionary and fascist coup carried out in July 1936. The united front strategy also helped turn the PCE into a mass party, with more than 100,000 members shortly before the war (besides dozens of thousands in the recently created JSU, or United Socialist Youth). Because of this, the party achieved a prominent political position –to the point where it represented the stronghold for the defence of republican democracy in the following years.

(In the picture: Pepe Díaz at the centre, surrounded by Dolores Ibárruri, Pedro Checa, Luis Cabo, César Falcón, Antonio Mije, Rodrigo Lara and Jesús Hernández.)

More information in the booklet “De los orígenes a la lucha guerrillera” (“From the origins to the guerrilla struggle”).

Four words define the history of our party in this time period: repression, illegality, exile, and guerrilla.

Four words define the history of our party in this time period: repression, illegality, exile, and guerrilla.

Franco’s victory in 1939 extended and imposed a fascist dictatorship all over the county. Franco’s prosecution against the PCE was severe due to his profound anticommunism, but also because the PCE was the only organization that resisted against Franco’s fascism until the end.

A vast amount of Communist cadres were in jail even before Franco’s troops marched into Madrid due to their opposition against Coronel Casado’s coup and their defense of the legitimacy of Juan Negrín’s government. Other members, who could not exit Alicante’s port, were captured and held captive in the prison camps of Almendros and Albatera. Others risked their lives escaping and trying to reorganize the party in Madrid and all over the country.

With a lot of members executed or imprisoned, many young women assumed the important role of reorganizing the party in clandestine networks –whose goal was getting the party back on its feet and helping members who were imprisoned and in hiding. The risk they took was huge, because each clandestine network that was reorganized (whether local, regional or national: the Reorganizing Central Commission in Madrid, Heriberto Quiñones, promoted from either the interior or from exile) barely persisted. One by one, they were captured by the Political-Social Brigade and sent to a military tribunal, were most of them were sentenced to death by a court martial without any guarantee or right to choose an attorney.

Spain itself became an enormous prison under Franco’s regime: tens of thousands of Communists and hundreds of thousands of people were executed or imprisoned, underwent forced labor, had their property expropriated, and/or were sanctioned with severe fines. Those who were imprisoned tried to reorganize the party structure to keep their dignity as political prisoners, to coordinate internal and external solidarity through the Red Aid, to resist against Franco’s regime (through protests such as the hunger strikes carried out by women imprisoned in Las Ventas and Segovia). Moreover, they tried to help women prisoners with legal advice –since April 1939, one of these services was run by Matilde Landa, who was then imprisoned in Las Ventas and was later punished with a relocation to Mallorca’s jail).

Political prosecution was militarized up until Julián Grimau’s sentence in 1963. From that moment on, the Tribunal of Public Order was established. It was an exceptional body with civil judges, responsible of prosecuting political and trade union opponents –who were mostly members of the PCE and the recently created Comisiones Obreras (or Workers’ Commissions).

Those leaders and members of the PCE that could flee from Franco’s regime settled in the USSR (where the leadership elected under José Díaz lived –as he was replaced by Dolores Ibárruri after his death), France, French northern Africa, and Mexico. The PCE was isolated from the rest of Republican and left-wing forces for a while due to the German-Soviet pact in 1939, and due to the final confrontation between socialists and anarchists due to Casado’s coup.

Although the guerrilla was already active during the war and the beginning of the postwar, it was further developed –especially from 1944 on. Its members were people who were hiding in the mountains, together with guerrilla fighters who came from France. These had an extensive experience fighting against Nazi occupation through the Spanish Guerrilla Association (AGE, for its Spanish initials), who were mostly Communists and were part of the Interior French Forces. Once France was liberated, Spanish exiled Republicans expected that Western Allies would help them fight Franco’s regime –just as they had helped other guerrillas in other countries.

However, this support never came and the PCE organized thousands of guerrilla members in France to carry out the Operación Reconquista de España (or Operation Reconquest of Spain), with the invasion of the Val d’Aran in October 1944. Its failure led to the dissemination of its combatants all around the country, theoretically structured in six territorial groups, although they lacked coordination and one distinct operational command.

The heroic fight of the guerrilla and its network (mostly women) only brought imprisonments and executions, in the context of a dictatorship that became more and more powerful thanks to the Cold War. For that reason, in 1948 the PCE gave the order to stop the guerrilla struggle (although it lasted until the mid-fifties) and they began the strategy to infiltrate Franco’s regime unions.

During the Spanish Civil War, the PCE became a mass political party and the main actor against fascism and in defense of the democratic Republic. Unarguably, the PCE was part of an international structure, the Komintern; however, at the same time, it had to face a dynamic situation such as a war. The need to act and react in that constantly changing context made it hard for the PCE to follow the same tactics and political tempo required by Soviet strategy –as the USSR was mostly interested in preventing German expansionism by keeping the conflict in antifascist terms and by sustaining an international security joint system, in order to not alarm Western powers. For the first time in history, two communist ministers –Vicente Uribe and Jesús Hernandez– joined the Republican government. This was an internal decision, and as such it was not planned in the strategy designed by the International Communist, which preferred to give external support without participating in any government cabinet –as it was done in the case of the French Popular Front.

During the Spanish Civil War, the PCE became a mass political party and the main actor against fascism and in defense of the democratic Republic. Unarguably, the PCE was part of an international structure, the Komintern; however, at the same time, it had to face a dynamic situation such as a war. The need to act and react in that constantly changing context made it hard for the PCE to follow the same tactics and political tempo required by Soviet strategy –as the USSR was mostly interested in preventing German expansionism by keeping the conflict in antifascist terms and by sustaining an international security joint system, in order to not alarm Western powers. For the first time in history, two communist ministers –Vicente Uribe and Jesús Hernandez– joined the Republican government. This was an internal decision, and as such it was not planned in the strategy designed by the International Communist, which preferred to give external support without participating in any government cabinet –as it was done in the case of the French Popular Front.

Without ceasing to call itself a revolutionary party, the PCE became a solid bastion in the defense of foundational progressive republicanism. Against those tendencies pretending to realize the revolution from a micro perspective (radical transformations of the economy, the society, and the production relations at a local scale), Communists fully understood the macro perspective. They knew war was a total deathly fight, and they suggested the articulation of the tools they needed to face it: a popular and disciplined army, with a single command and a powerful war industry. In this process, the party had to face a threefold tension: it simultaneously had to sustain the government, compete for the left electoral spectrum, and restrain internal impulses from some of its radicalized sectors. It was all a difficult balancing act, and it was clearly evidenced in May 1937 and the months before Casado’s coup.

The PCE was a political party whose members grew exponentially during the war. However, it never made the qualitative leap to efficiently control and forge all those who wanted to join, and to transform all its members and supporters into an organized group of activists. It mobilized different layers of Spanish society around left-wing and republican values (democratic revolution, agricultural reform, rights for the working class, popular education, and youth and women’s rights). It rightfully became their greatest exponent, as it took a central position in war politics, harnessing the tools of mass mobilization in the context of a modern total war.

Its members and supporters came not only from organizations such as Amigos de la URSS, Socorro Rojo, Mujeres Antifascistas or the JSU, but also from socialists, left-wing republicans, and mostly from people without previous political affiliation, young people and women. Young men called up and mobilized, trained in active propaganda, and forged with the values of the new Popular Army. There were also women, who enthusiastically joined to fill vacant rearguard posts in factories and party cells.

For the first time in history, political commitment offered young women another way of life and sociability, far away from the traditional pillars: home, family and the church. Communist militancy offered many young women access to modernity under a Republic in war. This is the most significant aspect of the PCE –to the point it is safe to say that it was the most rejuvenated and feminized political party of the Republic during the war.

The PCE was a party that aspired to seize power, and it was a key actor in the main State apparatus. However, it had to leave behind all those aspirations due to the instructions of the Comintern and with the goal to keep pluralism in the Popular Front. In the end of the war, the PCE was the main force holding the government of Juan Negrín and its resistance politics. This event made the PCE earn the animosity of those in favor of the capitulation, who led to the collapse of the Republic in March 1939.

(In the picture: milicia members of the Fifth Regiment in the famous courtyard of the Salesian convent in Francos Rodríguez street).

Más en el cuadernillo "De los orígenes a la lucha guerrillera".

Discurso de José Díaz en 1936

La lucha por las libertades y en el movimiento obrero desde los años sesenta

En la década de los sesenta se produjo una notable revitalización de la lucha antifranquista, fuertemente intensificada, en la primera mitad de los setenta, con la crisis terminal del régimen. El principal desafío a la dictadura vino representado, entonces, por la movilización de la clase trabajadora, gracias a la conversión del incipiente fenómeno de las comisiones de obreros en el robusto y combativo movimiento político y social de las Comisiones Obreras. Pero también otras sensibilidades militantes y democráticas (estudiantil y, más tarde, cultural, profesional, vecinal y ciudadana, feminista, etc.) contribuyeron al cerco a la dictadura mediante un amplio tejido antifranquista progresivamente extendido, sobre todo en la zonas más dinámicas del país. Muchas mujeres, militantes o simpatizantes comunistas, participaron en estas luchas, constituyendo en 1965 el Movimiento Democrático de Mujeres como frente con un marcado carácter de clase y de solidaridad frente a la represión, que con el tiempo fue desarrollando también planteamientos feministas.

El PCE no fue el único grupo, pero sí el más persistente, activo y hegemónico en esta estrategia de lucha política y social. Decenas de miles de hombres y mujeres organizados en torno al partido y bajo su dirección, pese a los duros costes de la represión, supieron impulsar la lucha asumiendo con realismo las reivindicaciones inmediatas de la clase trabajadora e insertándolas a la vez en un horizonte de lucha por la democracia y los cambios sociales en el país.

Gracias a este dinamismo, el partido fue incrementando numéricamente su militancia e implantación y avanzando en su influencia social. Ni las crisis internas de dirección o las escisiones minoritarias, ni la competencia de otras fuerzas de la “izquierda radical” o grupos comunistas disidentes, impidieron este ascenso, cimentado en la profunda imbricación y los aciertos tácticos fundamentales en el movimiento obrero y los demás frentes de lucha. A la vez, continuaba el debate y la profundización sobre la “vía democrática al socialismo”, la necesidad de amplias alianzas sociales estratégicas (lo que se definió como confluencia de las fuerzas del trabajo y de la cultura) y la modulación de las tácticas en la acción política y social para poner fin a la dictadura.

Más difícil se evidenció la posibilidad de articular una amplia alianza política antifranquista, tanto por la debilidad de las demás fuerzas opositoras como por la falta de voluntad unitaria de las mismas. Y ello pese a que la propuesta unitaria, siempre amplia y flexible, se fue ensanchando hasta dirigirse a sectores “democráticos” de la burguesía y “reformistas” del régimen. Tal apertura fue facilitada con el llamamiento al Pacto por la Libertad (1969) y los cambios y propuestas del VIII Congreso (1972). La Junta Democrática, con sus méritos pero también sus limitaciones, fue, ya en 1974, en el contexto de la enfermedad del dictador, su principal plasmación práctica.

El crecimiento del partido y la formulación del esquema estratégico y táctico que cristalizó en el Manifiesto-programa de 1975, fueron paralelos al distanciamiento de la Unión Soviética y a las primeras críticas al modelo del llamado “socialismo real”. La crisis del movimiento comunista internacional y las condiciones de la lucha en los países europeos y de capitalismo avanzado alentó cambios en la política del partido, en continuidad acentuada con el viraje iniciado en 1956. La condena en 1968 de la intervención militar del Pacto de Varsovia en Checoslovaquia supuso un punto crítico de inflexión, generando conmociones y algunas fracturas entre la militancia. En los años siguientes, en sintonía con otros partidos comunistas de países próximos, coincidiendo con los comienzos de la Transición en España, el PCE formulará su propuesta de lo que se conocerá como eurocomunismo.

The history of the Communist Party of Spain begins in October 1917, when the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia. This event shook the foundations of capitalism and the international labour movement.

The history of the Communist Party of Spain begins in October 1917, when the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia. This event shook the foundations of capitalism and the international labour movement.

In 1919, the Communist International (Comintern) was founded in Moscow and it called for all working-class parties to join. Shortly afterwards, the youth branch of the Socialist Party agreed to join the Comintern, and as a result the Spanish Communist Party was founded in 1920. During the extraordinary congress of the PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), in 1921, the spokesperson for those in favour of joining the Comintern, Óscar Pérez Solís, said that the Spanish proletariat would walk “with unshakeable belief (…) along the rugged path of salvation” of the International. He finally joined the Comintern with the recently founded PCOE (Spanish Communist Workers’ Party).

The existence of two different parties posed a problem that was settled in November 1921, when the Spanish Communist Party and the PCOE merged and founded the PCE (Communist Party of Spain). With scarce territorial presence, its First Congress (1922) saw the adoption of very generic theses and the election of Antonio García Quejido as its General Secretary –a veteran labour leader from the old PCOE. The party had a limited number of members and sometimes these were blinded by the Bolshevik course of action. Therefore, it acted with the same leftist radicalism as the revolutionary trade unions from that period: spontaneity, indiscipline, violence and a certain apolitical instinct. The party defined itself as the representative and the vanguard of the working class, although it took many years for it to create a tool to develop its own trade union model.

Shortly after the Second Congress (1923), Primo de Rivera installed a dictatorship. This forced the party to act underground, which hindered its growth. In the Third Congress (1929), held near Paris, it loyally repeated the theses that came from the Comintern. The fall of Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship allowed the PCE to slowly recover its limited public presence, reaching 5,000 members in the early thirties.

The PCE welcomed the Second Spanish Republic on April 14, 1931 speaking out against the bourgeois republic and in favour of the soviets. However, the party didn’t have many members and it was defined by sectarianism, organisational weakness and poor theoretical reflection. Things turned around in 1932, when a new leadership was elected and José Díaz became General Secretary: the party abandoned sectarianism and its marginal influence to become, hand in hand with the Comintern, a real mass organisation.

[Photography taken from the newspaper edited by the Spanish Communist Party after the First Congress of the PCE. In the excerpt we can read: “Since, in spite of this tragic, wrecked and persecution atmosphere, and defying all kinds of dangers and surprises, the Communist Party of Spain (Spanish Section of the Communist International, or SEIC by its Spanish initials) has just held in the nation’s cap…”).

[Photography taken from the newspaper edited by the Spanish Communist Party after the First Congress of the PCE. In the excerpt we can read: “Since, in spite of this tragic, wrecked and persecution atmosphere, and defying all kinds of dangers and surprises, the Communist Party of Spain (Spanish Section of the Communist International, or SEIC by its Spanish initials) has just held in the nation’s cap…”).

Information taken from the booklet “De los orígenes a la lucha guerrillera” (“From the origins to the guerrilla struggle”).